EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Why poor families invest so little in preventive measures? One example is that staff at the health centres that are responsible for vaccinations are often absent from work. Banerjee, Duflo et al. investigated whether mobile vaccination clinics where the care staff were always on site – could fix this problem. The result– Vaccination rates tripled in the villages.

14 October 2019

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2019

to the following candidates

Abhijit Banerjee

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA

Esther Duflo

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA

Michael Kremer

Harvard University, Cambridge, USA

“for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”

Their research is helping us fight poverty:-

The research conducted by this year’s Laureates has considerably improved our ability to fight global poverty. In just two decades, their new experiment-based approach has transformed development economics, which is now a flourishing field of research.

Despite recent dramatic improvements, one of humanityHuman Ο άνθρωπος (Humanum> Homo sapiens) मानव:. We have failed to consider the minimum need to be a 'human'. For Christians, human beings are sinful creatures, who need some saviour. For Evolution biology a man is still evolving, for what, we don´t know. For Buddhist Nagarjuna, the realisation of having a human body is a mere mental illusion. We are not ready to accept that a human is a computer made of meat. For a slave master, a human person is another animal, his sons and daughters are his personal property. ’s most urgent issues is the reduction of global poverty, in all its forms. More than 700 million people still subsist on extremely low incomes. Every year, around five million children under the age of five still die of diseases that could often have been prevented or cured with inexpensive treatments. Half of the world’s children still leave school without basic literacy and numeracy skills.

This year’s Laureates have introduced a new approach to obtaining reliable answers about the best ways to fight global poverty. In brief, it involves dividing this issue into smaller, more manageable, questions – for example, the most effective interventions for improving educational outcomes or child health. They have shown that these smaller, more precise, questions are often best answered via carefully designed experiments among the people who are most affected.

In the mid-1990s, Michael Kremer and his colleagues demonstrated how powerful this approach can be, using field experiments to test a range of interventions that could improve school results in western Kenya.

Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, often with Michael Kremer, soon performed similar studies of other issues and in other countries. Their experimental research methods now entirely dominate development economics.

The Laureates’ research findings – and those of the researchers following in their footsteps – have dramatically improved our ability to fight poverty in practice. As a direct result of one of their studies, more than five million Indian children have benefitted from effective programmes of remedial tutoring in schools. Another example is the heavy subsidies for preventive healthcare that have been introduced in many countries.

These are just two examples of how this new research has already helped to alleviate global poverty. It also has great potential to further improve the lives of the worst-off people around the world.

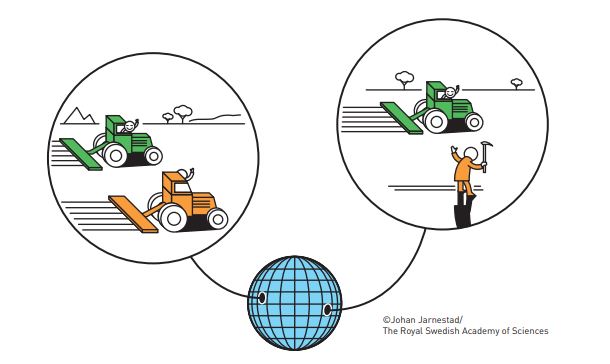

Illustration: Difference productivity

Illustration: Improved educational outcomes

Illustration: Vaccination rates

DOWNLOAD FOLLOWING DOCUMENTS TO UNDERSTAND THE RESEARCH

Popular science background: Research to help the world’s poor

Scientific Background: Understanding development and poverty alleviation

Abhijit Banerjee, born 1961 in Mumbai, IndiaIndia Bharat Varsha (Jambu Dvipa) is the name of this land mass. The people of this land are Sanatan Dharmin and they always defeated invaders. Indra (10000 yrs) was the oldest deified King of this land. Manu's jurisprudence enlitened this land. Vedas have been the civilizational literature of this land. Guiding principles of this land are : सत्यं वद । धर्मं चर । स्वाध्यायान्मा प्रमदः । Read more. Ph.D. 1988 from Harvard University, Cambridge, USA. Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA.

Esther Duflo, born 1972 in Paris, France. Ph.D. 1999 from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA. Abdul Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation and Development Economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA.

Michael Kremer, born 1964. Ph.D. 1992 from Harvard University, Cambridge, USA. Gates Professor of Developing Societies at Harvard University, Cambridge, USA.

The Prize amount: 9 million Swedish krona, to be shared equally between the Laureates

Today’s Nobel citation explains:

“More textbooks per student did not improve average test scores, but did improve test scores of the most able students. Giving flip charts to schools had no effect on student learning. The two health interventions reduced school absenteeism, but did not improve test scores. In theory, the incentive program could lead teachers either to increase effort to stimulate longterm learning or, alternatively, to teach to the test.

The latter effect dominated. Teachers increased their efforts in test preparation, which raised test scores on exams linked to the incentives, but left test scores in unrelated exams unaffected.

A field experiment by Kremer and co-author investigated how the demand for deworming pills for parasitic infections was affected by price. They found that 75 per cent of parents gave their children these pills when the medicineMedicine Refers to the practices and procedures used for the prevention, treatment, or relief of symptoms of diseases or abnormal conditions. This term may also refer to a legal drug used for the same purpose. was free, compared to 18 per cent when they cost less than a US dollar, which is still heavily subsidised. Subsequently, many similar experiments have found the same thing: poor people are extremely price-sensitive regarding investments in preventive healthcare.

Low service quality is another explanation why poor families invest so little in preventive measures. One example is that staff at the health centres that are responsible for vaccinations are often absent from work. Banerjee, Duflo et al. investigated whether mobile vaccination clinics – where the care staff were always on site – could fix this problem. Vaccination rates tripled in the villages that were randomly selected to have access to these clinics, at 18% compared to 6%.”